Roughly 5,000 years ago Egyptians invented papyrus and ink. It’s said the twin technologies revolutionized the world, allowing collective human thought to be shared and spread with relative ease. But how did the Egyptians create their distinctive black inks? Researchers from the Universities of Copenhagen, Mexico and the Sorbonne have teamed up with scientists from the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility to find out.

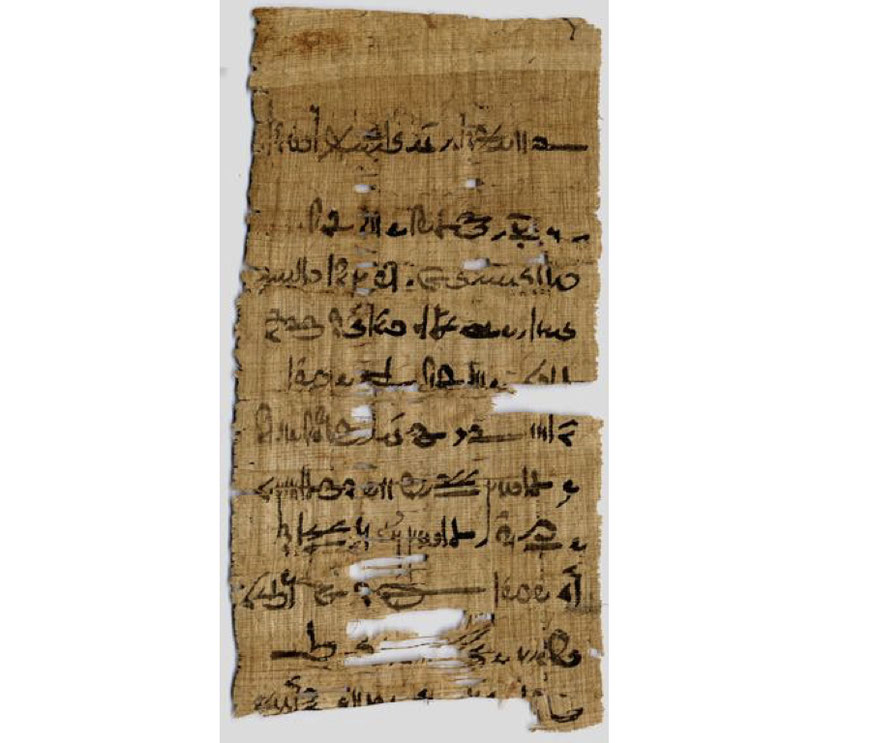

The group analyzed papyri fragments from the Papyrus Carlsberg Collection, University of Copenhagen. The fragments were part of manuscripts derived from two sources: Horus, an Egyptian soldier stationed at Pathyris (roughly 18.5 miles south of Luxor) sometime before 88 BCE; and from the Tebtunis temple, which according to the research group, is the only large institutional library to survive into modern times. Ultimately the samples chosen represented a 300 year time span and distinct geographical regions.

After obtaining their samples, the scientists turned to the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) to explore the chemical composition of the ancient ink. A synchrotron is a gigantic machine (ESRF says theirs is “stadium sized”) that speeds up electrons, directs the light they emit into “beamline” laboratories, and basically creates an x-ray image on steroids. Scientists are able to see whatever they are studying on an atomic level.

Synchrotron analyses showed all of the inks, regardless of age or geography, contained copper and the group says, the “soot/charcoal” that made the inks black were likely created by extracting copper from specifically chosen raw materials. The researchers say their findings are in keeping with other studies showing ancient Egyptians made blue inks by mixing copper oxides with a variety of raw materials typically found in Egyptian glass workshops.

However, despite consistency in production techniques, the group found that none of the black inks they looked at were exactly the same. In fact, lead researcher Thomas Christiansen said in a statement,

“…there can even be variations within a single papyrus fragment, suggesting that the composition of ink produced at the same location could vary a great deal. This makes it impossible to produce maps of ink signatures that otherwise could have been used to date and place papyri fragments of uncertain provenance.”

"However, as many papyri have been handed down to us as fragments, the observation that ink used on individual manuscripts can differ from other manuscripts from the same source is good news insofar as it might facilitate the identification of fragments belonging to specific manuscripts or sections thereof."

The research team believes their findings will be of greatest use in conservation efforts. They say that if conservators know the chemical composition of ancient materials, then tailored preservation strategies, which hopefully will preserve artifacts well into the future, can be crafted.

The group published a paper detailing their methods and findings in Nature’s Scientific Reports.