Corpses, cannibals, and cups made of skulls. Such was the reality 14,700 years ago in Somerset, England according to evidence unearthed in Gough’s Cave.

According to Silvia M. Bellow of London’s Natural History Musuem, Gough’s Cave, part of Cheddar Gorge, in Somerset, England, has been periodically excavated since the 1880s and in that time has yielded one of the largest sets of Magdalenian Period (17,000 to 12,000 years ago) human remains ever found.

Bellow says there is “unequivocal evidence of nutritional cannibalism” at the site, pointing to research undertaken by paleontologists who found that shortly after death, corpses were scalped, dismembered, and filleted, and skulls were taken apart so that only the cranial vault remained. Cranial vaults, biologically home to the brain, were painstakingly shaped to remove broken edges, turning them into skull-cups.

Adding an extra twist to an already extraordinary tale, Bellow and her research group have discovered designs engraved in cannibalized bone recovered from the cave site.

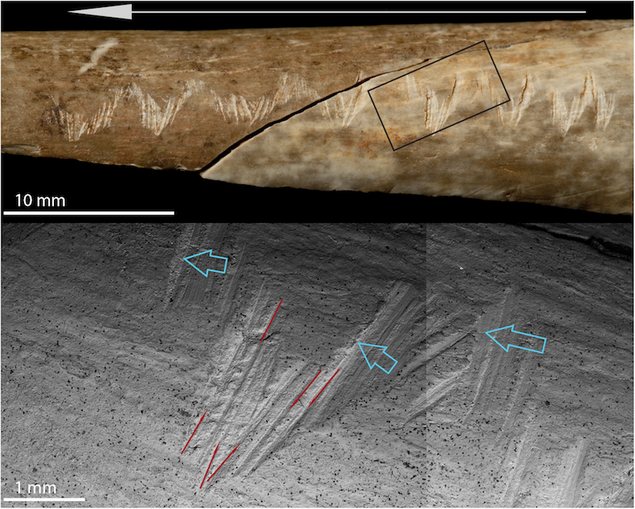

Using a scanning electron microscope and 3D renderings to examine cut marks left on a radius (arm bone) recovered from the cave, Bellows and her team found the cut marks were from engraving rather than butchering and that they formed a pattern consistent with Magdalenian period motifs.

The group also discovered the radius was smashed to gain access to the bone marrow and that it was chewed, leaving human teeth marks on the surface of the bone.

Bellows and her team say the radius was engraved before it was smashed and that one person, using one tool, likely did the engraving after the bone was scraped clean of flesh. They say the steps taken by the Gough’s Cave people from start to finish suggests bone engraving was an integral part of “the multi-stage cannibalistic ritual.”

No one knows the meaning or purpose behind the engravings, but Bellow and her team say the engravings may have served as a memory of the deceased or even of the ritual itself. Whatever the reason, the team points out the engravings were not meant to last. They were quickly executed and then discarded.

Nonetheless, Bellow’s group says the act of engraving the bone was likely an important part of the overall ritual and helped to form a “complex cannibalistic funerary behavior” never before seen in the Paleolithic.

The group published their work in PLOS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0182127.