Researchers at the University College London (UCL) have figured out why we humans have dedicated sex cells and normal body cells. Now if you’re like me, your initial thought is “because we have babies with sex cells, duh,” but as it turns out there’s a lot more to it. Humans and mammals in general form sex cells early in life (so they get to be called a “germline”) and separately from the cells that makeup our bodies. Plants and other simpler life forms on the other hand, produce sex cells later in their life cycles and from normal body cells. No sandboxing there.

So why do mammals do it differently? At first researchers speculated that the complex tissues mammals build for their complex parts like brains, spawned germline sex cells. But the UCL research shows that in reality, creation of a germline came down to mitochondria, the little powerhouses of cells.

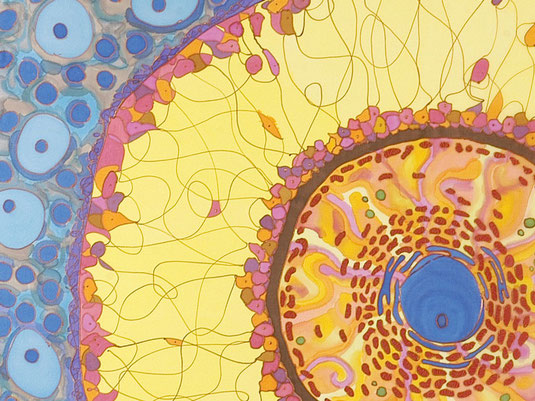

Quality mitochondria are essential to a creature’s survival because they provide energy for cells without which, the cells, and then by extension the creature, dies. So if bad mutations start creeping into mitochondria that’s passed onto offspring, then the offspring are likely not going to make it. Plants and simple organisms have very slow mutation rates though, so for them a system of using body cells to create offspring later in life is one that works. Mammals are different.

Mutations find their way into mammalian mitochondria pretty quickly because of our higher metabolic rates. Therefore, if mammals used body cells to reproduce, those cells would have been through lots of divisions by the time they were needed and the potential for mitochondrial errors would be high. Enter sandboxing in the form of a large egg. Mitochondria is so important to life that it is only passed on to the next generation through female egg cells, no sperm allowed.

It’s a pretty cool thing. One of the study’s co-authors, Professor Andrew Pomiankowski (UCL Genetics, Evolution & Environment) said of the findings,“Without a germline, animals with complex development and brains could not exist. Scientists have long tried to explain the evolution of the germline in terms of complexity. Who would have thought it arose from selection on mitochondrial genes? We hope our discovery will transform the way researchers understand animal development, reproduction and ageing.” And we here at the Almanac learned something we didn’t even know we didn’t know.